Five years ago, Zakiya Esper, then a juvenile probation officer, tired of funneling kids into ineffective programs. Fueled by her own story of struggling in college but finding a career, she took a leap of faith and created a nonprofit focused on interrupting the school-to-prison pipeline.

By Megan Parrott

May 5, 2018

As you have a conversation with Zakiya Esper, you quickly get the sense you’re talking with someone who has realized her purpose in life and had the courage to act on it.

“I think I try to create spaces where people feel safe and I try to get to know people well enough to understand what makes them feel unsafe,” Esper says.

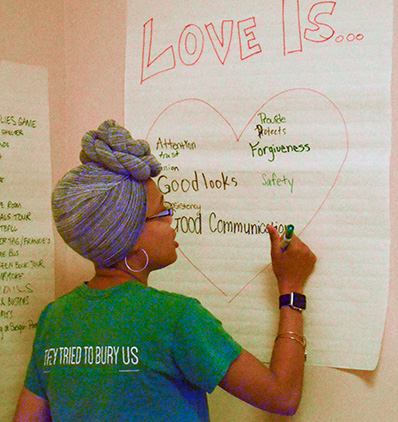

Esper is the moving force behind Sowing Seeds into the Midlands with a mission of creating a safe place for youth and keeping them out of the juvenile court system.

After spending three years as a juvenile probation officer, she says, she reached a point where she could no longer keep funneling kids into programs that weren’t working to help them.

“It was clear that I wasn’t helping and we were doing our young people a disservice by saying, ‘Here’s what you need,’ knowing it’s not there and then punishing them for not recovering when we didn’t give them what we said they needed,” she says.

So in 2014 she took a leap of faith to create the nonprofit Sowing Seeds to support those the system labels “deviant” or “delinquent.”

Everyone should know that Esper is “here to stay,” said Megan Plassmeyer, community engagement coordinator for the S.C. Women’s Rights and Empowerment Network, who worked with Esper this past summer.

“This is a long-term mission that’s rooted into the community,” Plassmeyer said. And Esper, she said, never makes other feel unwelcome.

“She’s very relaxed, bubbly, engaging, and the youth love her and the rest of the community does too,” Plassmeyer said.

For those who know Esper, helping others is intertwined with her personality. They say she has a habit of looking past what you’ve done and, instead, considers all your potential.

Although “at risk” often labels the children she works with, Esper won’t use it.

“If someone labeled me based on something I did, that would be pretty messed up,” she says. “I would rather people refer to me as who I am. I am who I am, not what I’ve done.”

Columbia Voice sat down with Esper to learn more about the woman behind the mission. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. (Listen to the entire interview.)

So I’ve been told that you have a personality that makes everyone feel welcome. Is that on purpose?

I don’t think so. I don’t know, I’ve never been told that. … I think I try to create spaces where people feel safe and I try to get to know people well enough to understand what makes them feel unsafe. … So I guess on purpose, but I didn’t realize and I’ve never heard it that way. …

You’ve done a lot so far to help others. When do you say to yourself, “Yeah I’ve been successful”?

I don’t feel that I’ve done nearly enough. … I try not to quantify, oh onceI’ve reached 1,000 kids then I’ve been successful. I really see my young people that we work with as individuals, and they have individual needs and they’re all still growing. … I think this journey that we’re on to try to interrupt the school-to-prison pipeline, I think until it’s interrupted completely, until kids are able to live and be in a space where they’re not gonna be criminalized for being kids, we haven’t been successful. I think we have a long way to go. …

Links

|

Speaking of, the school-to-prison pipeline seems to always trigger something inside you. What is it about you that almost compels you to focus on it?

I think that the opportunity that I had to see how it works in action when I was a probation officer. Before I got that job, I had this idea of what it meant to be a kid who’s involved in the justice system. I thought it was these kids who maybe came from bad homes and who were doing these, making these really terrible mistakes and just egregious behavior, and then when I got in there I got to know these kids and I was like, these kids are just like me and my friends when we were in school. …

That is what compels me, and that’s why I’m sorta triggered because I’m like, no that could’ve been me. … The children that are most affected by the school-to-prison pipeline are black and brown youth, and so I’m a black person and my children are black people and I have black and brown cousins and friends, and for me, it’s such an obvious infringement on their rights because of their skin color. … But also, it’s just so obviously unfair when you get a front row seat, but when you can’t see it from the front it kinda looks like well, bad kids, bad kids have to be punished. There has to be consequences. But right up close it’s so obvious that these are just kids and that’s not illegal. …

What do you think has been the defining moment in your life that has brought you to where you are?

Getting kicked out of college. No doubt about it. … I went to the College of Charleston, it was the No. 1 party school in the nation when I started as a freshman. By the end of my sophomore year, I don’t even know what my GPA was, but it was close to nonexistent. It was not really a number because I was having a very good time, and I got an email that said don’t come back. …

I got a phone call from a mentor, I had a mentor who worked at the college, and he taught diversity and inclusion classes, so he did workshops and things like that with us. … He called me and he said, “Hey, I heard you got kicked out of school,” and I was like, uh, yeah I did. … and he was like, “Come over here and work for me. I’ve got this new job working at Florence Crittenton Programs of South Carolina.” … So I went, worked for Greg, fell in love with the work. … I wrote the college a letter and sad hey, guess what I’ve been doing for six months. … And they let me back in, and I finished, graduated, and now I’m running a nonprofit. So I tell that story because I think it’s so important for us to talk about redemption opportunities for, not just teens, for everybody.